Attention!

The content on this site is a materials pilot. It represents neither changes to existing policy nor pending new policies. THIS IS NOT OFFICIAL GUIDANCE.

Learning Cohorts

A learning cohort is a group of people who come together to transform their foundational knowledges and practices. It might be two or twenty people, but 3-8 people working and learning together represent an optimal size when it comes to having a diversity of ideas while, at the same time, creating space for every voice to be heard.

These learning materials are structured with the intention that small groups of people will engage in learning and transformation in community with each other. What follows are the principles and practices that guided the design and development of the State Officer, M.D. course.

Learning as a tool for organizational transformation

The MES Team is shifting the oversight of state MES investments toward a more outcomes-oriented approach. We believe this will improve Medicaid IT’s direct support of program needs and ongoing compliance with federal policy requirements. This shift requires a significant cultural change in how the MES Team and State Officers engage with states. A plan for learning new ways of engagement is pivotal to the success of this effort.

Learning cohorts provide a model for professional development that encourages the following values:

- Dedicated time to dive deep into learning is a part of the State Officer job and work week.

- Discussion and sharing of personal experiences helps us learn new principles.

- Small communities (6-8 people max) are best for supporting learners and encouraging mutual accountability as they engage in learning and transformation.

- Individual preparation and reflection enhances group discussions and knowledge exchange.

- Learning and developing are a continuous process. It takes time and community support to develop new ways of working and thinking.

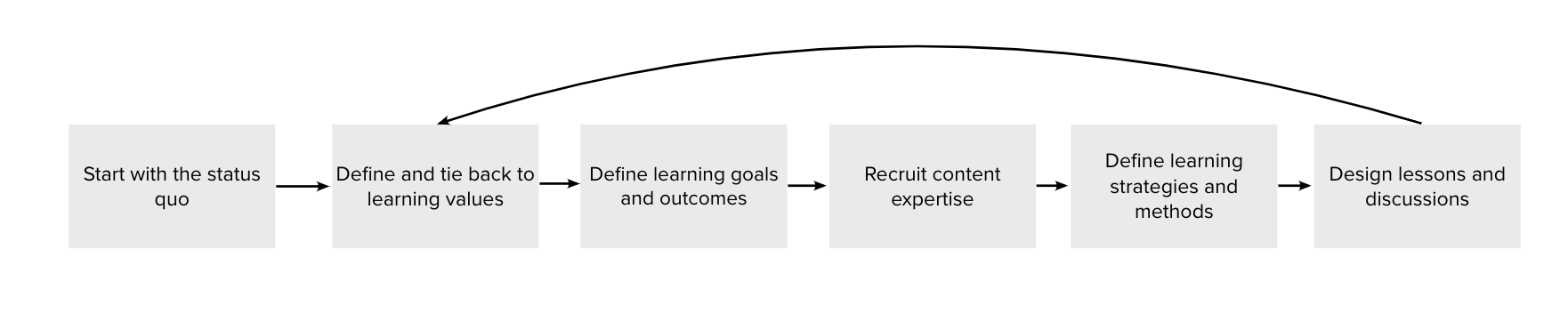

Developing a Learning Cohort

Organizing a learning cohort and their learning is broadly referred to as instructional design. It’s not very different from other design processes, and routinely involves large numbers of sticky notes. Like all skills, designing and facilitating educational experiences is a practice in which expertise is developed over time.

With that in mind, there are common components that will be needed for any learning cohort. We’ve broken them down below based on what is tangible and seen by learners versus built, designed, and decided on behind the scenes. We’ve also provided examples of how we applied these for State Officer, M.D. (SOMD):

Start with the status quo

It is important to explicitly call out the status quo when we talk about learning and instruction. To make a parallel with IT systems, this is like acknowledging that the dominant model for IT procurement has led to spending increasingly large amounts of money on ever-fewer vendors, ultimately yielding a situation where projects have a high risk of failure and the government has little control over their systems and process.

In the context of instruction and learning, we remain culturally dominated by the industrial model of instruction. This is the belief that we can put 60, 100, or more students in a room, lecture at them with content, and they will “learn.” This model works for some kinds of content and for some kinds of learning. If your goal is to remove workers from the classroom by age 14 and get them in front of an industrial loom or cranking a lathe for the next 50 years, this works great.

As people who grew up in the United States, much of our instruction was in schools that have seen consolidation-after-consolidation, yielding fewer teachers, larger classrooms, and a continued emphasis on testing of knowledge (as opposed to learning to think). Therefore, as instructional designers—as people working to inspire cultural change and reflective practice by and between our colleagues—we must de-program ourselves from the models we grew up in, and help our colleagues see the value instruction that move us from “the sage on the stage” to “the guide on the side.”

Resources

- Pressbooks has a free, online text regarding “flipped design,” or “learner-centered design” that provides an overview of instructional design.

- Reigeluth’s Instructional-Design Theories and Models is considered seminal in this space.

Define learning values

Education is extremely value-laden. This is because learning is such a fundamentally human experience, and we are all complex, changing, value-laden beings.

As an organization, knowing what you value or what values you aspire to is critical. Do you value a community of State Officers who trust, support, and work with one another? If you do, then the learning experiences you provide need to mirror the culture and community you wish to foster and develop, and through that learning, reinforce the habits of mind and practices that will yield to the community of practice that you envision.

Resources

- There are many instructional design models. Different models center values (their solicitation, explication) differently. Knowing what you value allows for the alignment of values with the design framework you employ.

- John Dewey was a modern educational philosopher whose writing is as relevant today as it was 100 years ago. He wrote extensively about the many facets of values in educational systems. A full chapter of Democracy and Education is devoted to discussion of values.

Define learning goals and outcomes

Values drive goals. For example, valuing community implies learning goals regarding communication and collaboration. Goals are overarching statements made as part of an instructional design process. Outcomes are the assessable, measureable products of learning experiences.

“Measurable” here does not necessarily mean we score everything as an “A,” “B,” “C,” or on a 100 point scale. Assessment of learning is (surprise!) exceedingly complex. “Measurable” does generally mean observable. For this reason, avoid learning outcomes like this:

State Officers will understand the importance of clear communications.

Instead, state something we can observe:

State Officers communicate with each other multiple times per day using plain language.

The important distinction is that we cannot observe understanding. However, we can observe communications that occur frequently and in plain language. In short, good assessment will align with your values and goals, and be tied to easily observable behaviors that exemplify the spirit of those values and goals.

Resources

- The CDC’s Developing Program Goals and Measurable Objectives is about programmatic development, but applies nicely to instructional design.

- Elgin’s distance education unit provides a concise overview of goal and outcome development.

- Pitt’s learning support center gets into the nitty-gritty of developing goals and LOs.

Recruit content expertise

It is common for people to believe that good instruction is all about the content. It is important for instructional designers to work with SMEs, or have content expertise themselves, but it is unlikely that becoming a field-leading expert is the end-goal of a learning experience.

In the development of the SOMD course, our team had people who both had expertise in the design and development of educational experiences as well as expertise in content regarding software systems design and implementation. However, there are lessons that leveraged SMEs for content, and the learning environment then was “wrapped around” the value they brought to the process. (The lesson on QASPs is a good example of this.)

MES has a great deal of internal content expertise. How that expertise is transformed into learning (and, through it, cultural change) can be accomplished in many ways. The MES team might grow instructional design expertise internally; they might hire in a new team member to lead ongoing instructional development/cultural change efforts; or, the team can work with vendors to provide ongoing design and delivery of learning experiences. Regardless, the team needs to know what they value and be thinking about what they might observe (measure) about the learning that their teams are engaged in.

Resources

- Educating for an Instructional Design and Technology Future, Irlbeck, Journal of Applied Instructional Design

- 11 Top Instructional Design Skills, DiFranza, Northeastern University Graduate Programs Blog

Define learning strategies and methods

With values, goals, and outcomes in hand, and content expertise in the wings, effective instructional design will now grapple with instructional strategies and methods. As suggested earlier, instructional strategies must align with:

- The values articulated by the organization.

- The goals for the people engaged in the learning.

- The outcomes that are desired.

- The content to be articulated in support of those values, goals, and outcomes.

If MES values collaboration and communication amongst the State Officers as part of their work, then it may be that instructional strategies that explicitly require collaboration would be preferable to approaches that emphasize independent learning by the SOs. Or, even if SOs come together in a group, an instructional approach that centers an instructor conveying content will fail to reinforce those core values that undergird trust and community.

Put simply: the right instructional methods will achieve desired learning outcomes and reinforce the values that drive your culture-change process.

Resources

- Instructional Design Strategies and Tactics, Leshin, Pollock, & Reigeluth

- Effect of Instructional Design Strategies on Self-Regulation of Learning, Perera, Pathways to Open Educational Practices. (This entire text is Creative Commons licensed, was published within the last year, and an excellent resource.)

Developing a lesson

As with any design process, the product—the lessons and learning experiences themselves—are the last thing to be generated.

In the case of the SOMD course, the design and development process behind the Health Rubric, the development of the Health Tracker, and the many interconnected efforts between the MES team and 18F deeply informed the work that went into the course.

Each lesson in the SOMD course follows a common template, for the simple reason that the consistency of lesson structure is intended to reduce barriers to learning for the State Officers. However, it is not a template that necessarily works for all learning situations, nor does it support all values, goals, and outcomes that might be imagined for other/future learning environments. In the case of SOMD, each lesson was expressed roughly as follows:

Laying the groundwork for discussion

In order to make the most of the time together as a cohort, each lesson included materials to introduce the learning outcome and content to add background context and details to a specific row in the Health Rubric. State Officers were asked to read/watch/listen, apply, and reflect on these materials in preparation for group discussion. These materials roughly followed the below outline:

- Restates the learning outcome (aligned directly with a row of the rubric)

- Introduces the SO to content related to the learning outcome.

- Asks questions to engage the SO with the content in a manner that connects it back to their professional practice.

- Sometimes, active techniques, like writing to think are employed, and other times SOs are encouraged to partner with others, thus leveraging think-pair-share or similar pairwise/small group learning strategies.

- Reflection and preparation is explicitly encouraged in advance of group conversations (readying the learner for analysis and evaluation of their learning in concert with others)

To lay the ground for group discussion and give State Officers time to reflect, the above materials were distributed the week before the lesson.

Learning as a community

When the group got together, facilitated conversation dove into the material to encourage processing as a group, again with a common structure:

- A centering exercise, to bring the group to the learning context (and step away from the activities of the previous minutes, hours, or days)

- A space for questions about the material and activity itself.

- A conversation around 1, 2, or more planned questions that focus the group on the similarity or differences of their experiences (in practice) with this dimension of the rubric and the content they have engaged with.

- Sometimes, for coverage, small-group techniques are employed; these provide greater confidence amongst learners for reporting out, as well as providing more opportunity for everyone to be heard in the learning context.

- Opportunities for expertise to emerge from within the group as well as from SMEs is provided throughout the conversation.

- A conclusion or “wrap up” that affirms the power, importance, and excellence of the learners is provided. Positive reinforcement of the learners, their efforts, and their work in community with each-other is essential (and reflects the values and goals of the learning environment as a whole).

After each group conversation the facilitators set aside 30 minutes to debrief on how the discussion went and what changes may improve future discussions or materials.

Assessing learning

The initial learning cohort did not emphasize the delivery of products from the learning, and does not have clear, measurable behaviors for assessment. This is a conversation that needs to be had, as there are many, many ways to measure what is going on with the SOs as they engage with material. Some of those will support the learning and cultural transformation that the course is intended to foster, and others will actively hinder the transformations MES hopes to encourage. Hence why the assessment of programs and learning alike are so complex.

Resources

- Designing Criterion Referenced Assessment provides an overview of an alternative approach to traditional modes of assessment known as criterion-referencing, whereby clear, measurable criteria are used to set transparent and achievable learning outcomes in concert with the learner.

- Instructional Strategies: The Ultimate Guide, Persaud, Top Hat Blog.

Equity and justice in education

Teaching and learning are fundamentally human acts: we engage in learning from the moment we are born and we pass our knowledge from generation-to-generation, through all that we do. It takes explicit work on the part of the instructional team to create learning spaces that are fundamentally empowering and inclusive. How we frame our instruction can include or exclude.

There is more to be said on equitable and just instructional design than can be hinted at here. Materials must support all learners, which means being conscious and attentive to how bias and discrimination casually creep into an educator’s practices. Learners must ask questions of the course material itself as well as the reality of racism, sexism, and their work as agents of the US government. This questioning should occur constructively and critically, on an ongoing basis. State Officers should be lifted up during this process, as these questions and their work thread a difficult needle—they are worthy of all of our support and respect as they work to transform the systems that make up our nation’s healthcare safety net.

Resources

- Structure Matters: Twenty-One Teaching Strategies to Promote Student Engagement and Cultivate Classroom Equity, Tanner, CBE Life Sciences Education. This article is essential; if you read nothing else cited in this document, read Tanner’s article.

- Teaching to Transgress lays a foundation for thinking about what it means to bring love to the act of teaching and learning. bell hooks remains one of our great moral and educational philosophers, a Black woman of incredible foresight and compassion whose philosophy on teaching and learning we cannot recommend highly enough.

- Teaching Community and Teaching Critical Thinking complement Teaching to Transgress, and take those ideas even further.

Conclusion

Instructional design is a field that is deep, wide, and has its roots in educational psychology and the study of teaching and learning. The development of the course for State Officers touched on all of the dimensions described above and more, and did so in a largely invisible manner. We believe that learning is a powerful vehicle for the transformation of practices and organizational culture, and are excited to support MES in this critical, ongoing work.